Memorandum submitted to the UK Parliament by Professor Vernon Bogdanor

(CBE, Professor of Government, Oxford University )

I. There is clear evidence that the European Union is losing

democratic legitimacy. It faces the challenge of harnessing popular

sentiment to the construction of Europe. That

challenge can best be met by adapting British ideas of responsible government

to the working of the institutions of the Union; and by introducing a measure of direct democracy, in the form of the

referendum, not to overcome the institutions of the Union,

but to supplement them.

II. It has become a commonplace that the European Union is

suffering from a democratic deficit, because the European Parliament is unable

to hold the executive of the European Union to account. Much of the

reform agenda which European leaders are preparing for the next

intergovernmental conference in the year 2004 is devoted to the internal relationships between the institutions of the European Union

and the appropriate balance between them.

The main problem

facing the Union, however, is less an

imbalance between the institutions than popular alienation from its objectives.

Indeed, this alienation is coming to threaten the very legitimacy of the Union itself. It is a striking fact that turnout

for the European Parliament elections has fallen steadily and continuously

since 1979, the year of the first European Parliament elections.

TURNOUT IN

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT ELECTIONS, 1979-99

In the last

elections in 1999, fewer than half of the eligible electorate voted; and this

figure itself overstates the true level of voluntary participation, since

voting is compulsory in Belgium,

Greece, Italy and Luxembourg.

In the two countries which are seen as the

motor of European Union, France and Germany, turnout was 47.0 per cent

and 45.2 per cent respectively. In the three new member states, Austria, Finland

and Sweden,

which voted for the first time in European elections, turnout was, respectively,

49.0 per cent, 30.1 per cent and 38.3 per cent. Turnout was lowest in Britain at 24

per cent. In parts of Liverpool, turnout was

just 8 per cent. Turnout in Britain,

it has been pointed out, was lower than the percentage who were prepared to

"vote" in a popular television programme called "Big

Brother". It is hardly possible for the European Parliament to claim a

mandate to represent the opinions of 370 million people of the European Union

when fewer than half of its eligible electorate is willing to vote for it.

This fall in turnout is paradoxical, since it

has occurred at a time when the power and influence of the European Parliament

have greatly increased, largely due to two major amendments of the Treaty of

Rome, the Single European Act of 1986 and the Maastricht Treaty of 1992. In 1979, at the time

of the first direct elections, many commentators, dismayed by a turnout far

lower than they had hoped, claimed that apathy was inevitable at a time when

the European Parliament had so few powers. Voters could not, they suggested, be

persuaded to turn out to elect what would prove to be little more than a

talking shop. However, the increase in powers for the European Parliament has

coincided with a steady decrease, not an increase, in the percentage of European

electors willing to turn out to vote for it. There is

thus a striking contrast between the progressive transfer of competences to the

European level and the lack of popular involvement on the part of the European

electorate. This failure to mobilise popular consent is now the principal

weakness of the European project.

There seems, then,

little enthusiasm for the European electoral process. Not only is the European

Parliament unable to help create a European consciousness, but, far from being

seen as the protector of the citizen against the machinery of European bureaucracy,

it has come to be regarded rather as part of that machinery itself. Instead of

being a counterweight to the technocratic elements in European Union, it is

perceived as an element in that technostructure, part of an alienated

superstructure.

This failing on the part of the European

Parliament, so it is suggested, is not contingent, but inherent in the way that

European institutions have developed since 1958 and on the tacit understandings

which underlie them.

The European Parliament stems from the Common

Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Community set up in 1952, which was

restricted to the exercise of largely "supervisory" powers. It was

not at the time seen as central to the European project, but was tacked on to

the other institutions of the Community in a somewhat perfunctory way. In the

Treaty of Rome, as ratified in 1958, the powers of the Parliament were

described in Article 137 as "advisory" as well as

"supervisory". The European Community,

then, was to be based not on parliamentary government, but on government by wise men and

women situated in the Commission, which was perhaps seen as a European analogue

to the French Commissariat du Plan.

The European Union has been very much

influenced by the ethos of consociational democracy.

This is little understood in Britain

where the ethos of the Union

is often, and in a rather facile manner, compared to that of a federal state. In a consociational state, however, as it existed in

the Netherlands, for example, politics operated by

elite agreement, and the various groupings forming the consociation—in

the Netherlands, Catholics Protestants and Liberals, in the European Union, the

peoples of the member states—remain separate. In such

a consociational system, the legislature foregoes much of its classical

role of scrutinising government and holding it to

account. For neither the legislature nor the

people dare untie the packages agreed by elites, since it is elite agreement which holds the system together.[1]

What both the French

technocratic ethos and the Dutch consociational

ethos have in common is their denial of the

basic principle of parliamentary government,

that government should be responsible to parliament. For the French,

parliamentary interference would have ruined the European project, as it had

ruined the 3rd and 4th Republics. For the Dutch, parliamentary government would

have divided Europeans in an unacceptable way, and so hindered the prospect of

reaching agreement. Such ideas were, of course more plausible in a period when there was deference to political leaders, when the

leaders led and the followers followed. It has become less plausible in an era

when the leaders continue to lead but the followers decline to follow.

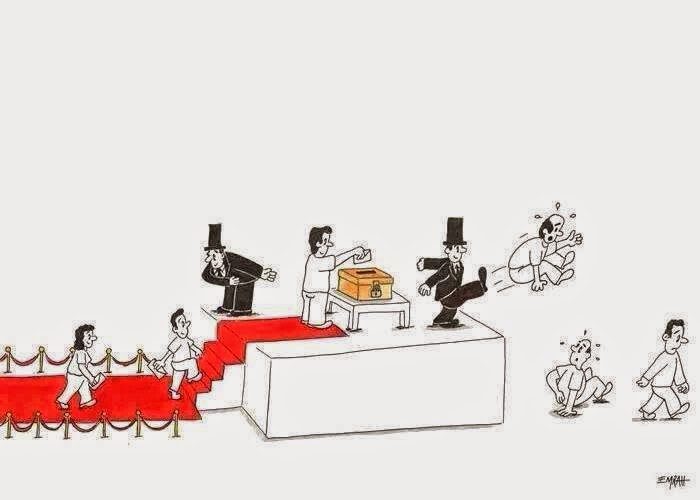

The consequence, however, was bound to be a restricted role for the European Parliament. Thus, elections to that Parliament do not, as we have seen,

fulfil the functions which elections are normally expected to perform.

In Britain,

and in most other democracies, elections confer

legitimacy because they fulfil three inter-related functions. They offer the voter first a choice of government,

second a choice of who should lead that

government, so providing it with a recognisable human face, and third the choice of a set of policies.

Elections to the

European Parliament, however, fulfil none of these functions. They do not determine the political colour of the European

Union, nor do they determine how it is to be governed, for the government of the Union

is shared between the Council of Ministers and the Commission, and the

composition of neither of these bodies is affected by European elections. Therefore

European elections do little to help determine the policies followed by the

Union; nor do they yield personalised or recognisable leadership for

the Union. This has important consequences

particularly in foreign policy. Henry Kissinger once

complained that if he wanted to telephone the spokesman for Europe,

he did not know what number to ring. "Who do I

call? Who is Mr. Europe? If I wish to consult Europe,

and I have a phone in front of me, what number do I dial?" At the time of

the Reykjavik summit between Reagan and

Gorbachev in 1986, Europe, whose interests

were clearly affected, was conspicuous by its absence. "Our old continent

is absent from the major negotiations between super powers at which Europe's fate is being sealed", the European

Parliament complained. "No single person is in a position to represent

it".[2] The situation is hardly different today.

The creation in 1999 of the post of Secretary-General and High Representative

for Commission Foreign and Security Policy, hardly fills the gap. Indeed, it is

doubtful if most Europeans know the name of the current incumbent, Javier

Solana, who was not, of course, chosen by anything resembling a democratic

process, and is therefore in no sense a political leader.

The Presidency of the European Commission is

decided not by the voters but by private dealings between the governments of

the member states. In 1994, for example, Jean Dehaene, the Prime Minister

of Belgium, who had been proposed as successor to Jacques Delors, was thought

to be unsuitable, not by the European Parliament, but by Britain's Prime

Minister, John Major, who believed that Dehaene was too "federalist".

Europe's leaders then agreed upon Jacques

Santer as his replacement. But this whole process took

place without any involvement or even consultation on the part of the European

Parliament, which, nevertheless, formally approved Santer as President.

Yet, Santer, who was a Christian Democrat

from Luxembourg,

was approved by a newly-elected Parliament containing a majority from the Left.

The European Parliament seemed perfectly prepared to endorse a President who

did not represent the majority of its members.

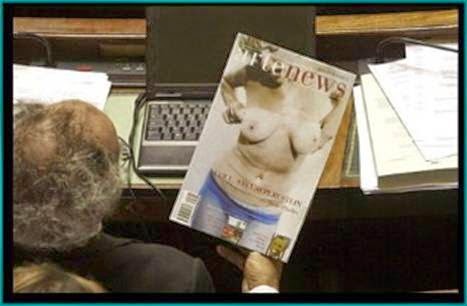

In March 1999, three months before the next

round of European Parliament elections, the European Commission resigned en

bloc, following allegations of corruption. This led to the replacement of

Jacques Santer as President of the Commission by Romano Prodi. It did not seem

to have occurred to the leaders of Europe,

meeting in private conclave, to await the result of the European Parliament

elections before deciding upon Prodi as the next President.

Moreover, the nomination of individual

commissioners by the member states bears no necessary relationship to the

electoral success of the political parties. In the 1999 European elections in Germany, for

example, the CDU/CSU, the German component of the Christian Democrat

transnational European Peoples Party, secured the largest number of votes, but

the SPD/Green government nevertheless appointed an SPD and a Green

commissioner. It would be difficult to find more

striking illustrations of the irrelevance of the European Parliament to the

governance of Europe, indeed of the

irrelevance of the elections themselves.

In elections in the member states of the

Union, electors generally sees a connection between their vote and the actual

outcome in terms of policy and leadership. Elections to the European

Parliament, however, do not lead to the choice of an executive nor of an

electoral college which chooses an executive. It is hardly possible, therefore,

for electors to perceive any connection between their vote and the policy of

the Union.

Thus elections to the

European Parliament, although in form transnational, have become in practice a series of national test elections,

analysed for their implications upon the domestic policies of the member

states, rather than the European Union. They are second-order elections in that

their outcome is dependent not on European matters, but on national party

allegiances, modified by the popularity or the unpopularity of the incumbent

government in each member state.[3] They thus bear some resemblance to

transnational opinion polls charting the fortunes of the main domestic forces in

the various member states. But this means that they

are unable to confer legitimacy on the European project.

III.

This weakness has become particularly striking since, in Europe, from the late 1960s, as in democracies in other

parts of the world, the demand for political participation has grown apace. One

consequence of this has been that the mismatch between popular expectations and

the performance of government widened during the 1980s and 1990s. For the

effects of social change—rising living standards, the gradual embourgeoisement

of the working class, the spreading ownership of property, shares and other

assets—all served to diffuse economic power more widely and to erode

traditional attitudes towards authority. The development of information technology

and the coming of an information society seemed to make possible a radical

dispersal of decision-making so that centralized, top-down methods of

government came to appear outdated. Many, perhaps most, democracies elected

governments which sought to move in the direction of a market economy

emphasising the importance of individual choice in both the public and private

sectors; one consequence was the development of a consumerist culture so that,

in social and economic affairs at least, the individual gained sovereignty. The governments of Margaret Thatcher and John Major,

moreover, sought to make public institutions themselves more accountable, both

through privatisation, and by encouraging devolution from local authorities to

individual institutions such as schools and housing estates. The central theme

was the attempt to give individuals more control over institutions providing

public services. Britain

indeed was a pioneer in the 1990s in a revolution in government and in

attitudes to government, a revolution which sought to resolve the paradox that

the triumph of liberal democracy, following the collapse of Communism, seemed

to be accompanied by growing alienation from government. If one had to sum up this revolution, one could say that its essence consisted

in government becoming more consumer and voter-friendly, more concerned with

outputs than inputs, more concerned to satisfy the needs of voters and citizens.

The "Citizen's Charter", introduced by John Major in 1991 was much

mocked at its inception, but its basic principle has been copied in a number of

other democratic countries. The reforms, sometimes rather superficially

attributed to "Thatcherism" were in fact widely adopted, even in

countries ruled by governments of the Left—France, for example, Australia, New

Zealand and Sweden.

Nevertheless, the growth of consumer

sovereignty was not in general matched by corresponding changes in the

political sphere. There was indeed something of a contrast between the return

of individualism in economic life and the relatively passive role which

individuals were expected to adopt towards their political institutions. Voters, however, have begun to show a disconcerting

insistence on untying the consociational packages that their leaders have

agreed. That process was apparent in the referendums on the Maastricht and Nice treaties in Denmark,

France and Ireland. It

might have been apparent in other member states also had they been required to

ratify these treaties by referendum. The packages agreed with much effort by

political leaders, therefore, are in danger of being untied as the demand for

popular involvement in decisions-making asserts itself. Perhaps indeed the concept of "consociational democracy" is

actually a contradiction in terms. Perhaps consociational systems only work by

denying democratic participation in what are seen as the wider interests of the

stability of the system. What is clear is that it is no longer, as

perhaps it may once have been, a satisfactory method of governing a community

whose members see themselves as active citizens.

Because the institutions of the European

Union are seen as being so remote from the voter, reforms involving rejigging

(rearrange) these institutions or inventing new institutions are unlikely to

prove of value. The European Union is already cluttered with institutions. It

needs a streamlining of institutions, and the reconnecting of its institutions

with the people, not more institutions.

The European Union has, in particular, no

need for a second chamber of the European Parliament, composed of national

parliamentarians from the member states. Such a second chamber which would be

analogous perhaps to the Bundesrat in the German Federal

Republic, or the American

Senate before direct election was introduced in 1913, would serve to impose the

pre-1979 European Parliament on top of the post-1979 Parliament. It would tend

not to the clarifying of accountability, but to the blurring of accountability,

since national electorates are already linked to the Council of Ministers

through their national political parties. The need

now is to link national electorates to the Commission through the transnational

political parties.

IV.

If, then, the constitutional structure of the European Union does not

yield accountability to the voters of Europe,

how might such accountability be secured? Some of Europe's

more far-sighted leaders have come to favor the introduction of an element of

direct election in European institutions. Ex-President

Giscard of France, for example, has advocated that the President of the

European Council be directly elected by universal suffrage, while Jacques Delors has

called for the direct election of the President of the Commission, and,

as a first step towards that aim, the election of the

Commission President by an electoral college comprising members of national

parliaments and the European Parliament. Jacques Chirac, also, has shown

considerable sympathy with the idea of direct election.

It is, perhaps, not at all surprising that

support for direct election comes from France whose 5th Republic finds so

important a place both for direct election of the President and for the

referendum. Indeed, it may be argued that if the European Community reflects in

part the ethos of the French 4th Republic, it should now be replaced by a

system based on the ethos of the French 5th Republic, and this is the aim of

the French reformers.

Direct election would explicitly recognise

the principle of the sovereignty of the people as the foundation-stone of a

united Europe. It seeks to

meet the central challenge facing Europe which

is that of discovering some means of bridging the

gap between the elite and the people so as to construct a European

consciousness without which the whole European idea will remain an empty

construct.

Direct election would enable European voters

to influence the policy of the European Union and to choose its government. It would provide that democratic base of legitimacy which

at present the European Union lacks. There would then be a strong

incentive for Europeans to vote in elections genuinely designed to determine

the political orientation of the Union.

Moreover, direct election would focus popular interest on European issues,

giving them glamour and excitement, qualities sadly lacking at present, and it

might therefore prove a remedy for falling turnout and electoral apathy.

But there are two obvious

objections to the idea of direct election. The

first is that European solidarity is probably not yet

sufficiently advanced for the nationals of one member state to be willing

to support the national of another as in effect leader of Europe.

Indeed, it may be argued that the proposal for direct election presupposes the

very solidarity which it is intended to help create.

Secondly, any

alteration in the method of electing the President of the European

Council or the Commission would require

an amendment to the Treaty. Such an amendment would need to be

carried unanimously by every member state. In two member states, Denmark and Ireland, Treaty amendment requires

approval by the people in a referendum. In both countries, referendums have led

to rejection—of the Maastricht Treaty in Denmark

in 1992, and of the Nice Treaty in Ireland in 2001. In another member

state, France, where a

referendum was not constitutionally required, the government nevertheless

called one on the Maastricht

treaty in 1993, and this led to but a narrow majority for the treaty. The two

rejections and the one near-rejection led to major crises in the European

Union.

It is highly unlikely that, in the current

state of Euro-scepticism, unanimous agreement could be secured for an amendment

proposing direct election of the President of the Commission or of the European

Council. At least one member state and possibly more, would probably reject

such a proposal, not only ensuring its defeat, but causing a further crisis in

the Union. This would reawaken the same

atavistic sentiments which Maastricht

aroused. The proposal for direct election is again seen to presuppose that very

European solidarity which it seeks to create.

But, if the French method of democratising

the European Union seems too Utopian to work in current circumstances, the same

may not be true for the British notion of parliamentary responsibility. Article 158 of the Treaty requires the President of the

Commission to secure a vote of confidence before assuming office. This vote is generally a formality, and it

would be refused only if someone manifestly unsuitable or corrupt were to be

proposed. There is no reason, however, why this should continue to be so.

There is no reason why the vote of confidence should remain a mere formality.

Instead, it could be used, as of course it is in Britain, to enforce responsibility.

In Britain, as in other parliamentary

systems, a government's existence depends upon its ability to secure a

majority in the legislature. If it fails to do so, it must resign. Why

should not the same principle apply in the European Union? The European

Parliament could, if it so wished, and without the need for any treaty

amendment, simply insist that the political outlook of the President of the

Commission, and indeed of the Commission as a whole, conform to that of the

majority in the Parliament. Thus, a Left majority could insist that the

President of the Commission and the Commission were taken from the Left, a

Right majority, conversely, could insist that the President and the Commission

came from the Right.

If the Commission were to be dependent upon

the majority in the European Parliament, this would entirely transform the role

of the Parliament, for it would become an executive-generating body. There

would then be an incentive for electors to turn out to vote in European

Parliament elections since they would be helping to determine whether Europe

was to be governed in a Leftward or a Rightward direction, something which has

become of much greater importance with the development of economic and monetary

union; electors would also be helping to determine the political leadership of

Europe and the broad direction of public policy in Europe. The elections

would become a real analogue of domestic elections rather than, as they are at

present, a series of domestic elections conducted simultaneously. Elections

to the European Parliament would fulfil the same three functions as domestic

elections. They would be helping to determine the broad direction of public

policy, choosing a government, to the extent that the Commission is in fact a

"government", and helping to determine the political leadership of Europe.

This transformation in the role of the

European Parliament would almost certainly lead to further consequential

changes. For voters would seek to know who the different transnational parties

would nominate as Commission President. The larger political groups would

probably nominate candidates for the Presidency before the European elections,

thus making the process of choice of President more transparent. This would

make the European elections in effect direct elections of the European

Commission. The analogy with domestic elections, which, in Britain and

many other democracies, have the function of directly electing the leader of

the government, would be even more complete. Direct elections would then

link voters to the Commission of the European Union through the transnational

parties.

The British contribution, then, could be to

show how the fundamental principle of parliamentary government, of a government

responsible to parliament, can be applied to the European Union so as both to

yield accountability and to clarify the purpose of European elections.

V. The idea of responsibility, however, implies not only the

responsibility of government to the legislature, collective responsibility, but

also the responsibility of individual ministers to the legislature, individual

responsibility. This too is an idea which could readily be adapted to the

European Union.

The essence of the notion of individual

responsibility was well stated by Gladstone who declared that "In every free

state, for every public act, some one must be

responsible; and the question is, who shall it be? The British Constitution

answers: `the minister and the minister exclusively'."[4]

Ministerial responsibility in this sense is a fundamental principle of the

British Constitution, defining and prescribing as it does the relationships

both between ministers and officials and between ministers and Parliament.

Indeed, it has the same importance in the British system of government as the

concept of the separation of powers does in the American.

Under the British system of government,

executive powers are, with a few notable exceptions, conferred by Parliament

upon ministers and not on officials. It is the concept of ministerial

responsibility which buttresses the politically neutral role of civil servants.

For it ensures that officials, with very few exceptions, speak and act in the

name of ministers. They have no constitutional personality of their own.

Everything that they do is, constitutionally, done under the authority of a

minister, either express or implied. Thus, civil servants are accountable only

to the ministers whom they serve. They have, in general, no direct

accountability to Parliament. Ministerial responsibility allows the minister to

be both the conduit through which accountability flows, and also the wall

protecting officials from Parliament. Thus, the concept of ministerial responsibility

sustains a structure of government within which ministers are served by

permanent officials who are required to serve governments of any political

colour, and who, at senior levels, are debarred from party affiliation. It is

in this way that ministerial responsibility helps to sustain a politically

neutral civil service.

The sharp separation of ministerial and

official roles which characterises Britain

and the "old" Commonwealth countries—Canada,

Australia and New Zealand—is not, by and large, met with in Europe. On the Continent, by contrast, there are

instead the phenomena of the elected official and the unelected politician.

Indeed, one of the reasons why we in Britain find it so difficult to

understand the European Union is that in it important decisions can be taken by

unelected persons, by European Commissioners. Jacques Delors, for example, a

European leader of great authority and significance, was never elected to any

position in the European Union, except the European Parliament between 1979 and

1981, when he left on being appointed Economics and Finance Minister in the new

government of Francois Mitterrand. Nor was he ever elected to any domestic

position, except in local government. It is little wonder that to British eyes

the operation of the European Union often seems to blur responsibility and to

confuse lines of accountability.

The

concept of responsibility both identifies who is under a duty to respond to

questions by Parliament, but it can also be used to attribute blame. Thus, the

principle of ministerial responsibility to Parliament prescribes, first, that a

minister must answer to Parliament for every power conferred upon him or her;

and second, that a minister is answerable to Parliament for the way in which he

or she uses his powers. Parliament can, in the last resort, if it is unhappy

about the way a in which a minister has exercised his or her powers, compel the

resignation of the minister.

There is a great contrast between the

principle of ministerial responsibility as it operates in British government,

and the absence of such responsibility in the European context. When, in 1999,

various commissioners were accused of mismanagement and corruption, the

European Parliament seemed to have no form of redress against the errant

Commissioners. The only form of redress was to secure the resignation of the

whole Commission en bloc, and that required a two-thirds majority in the

European Parliament. At one time, it looked as if an overall, but not a

two-thirds majority would be secured. This would have meant that the

Commission, despite having lost the confidence of the Parliament, could

continue, broken-backed, until the end of its term. But in any case the

resignation of the whole Commission would have punished the innocent along with

the guilty. It was as if in Britain,

the only way to punish a minister who had made a mistake was to require the

resignation of the government as a whole.[5]

To

introduce the principle of ministerial responsibility into the government of

the European Union would not, it seems, require any constitutional amendment to

the Treaty. It could be achieved if members

of the European Parliament were prepared to use their existing powers to the

full. In addition to a vote of no confidence in the Commission as a

whole, it would be perfectly possible for the European Parliament to put down a

motion of no confidence in a particular commissioner on the grounds of

mismanagement, incompetence or corruption, and to insist on securing access to

all the documents relevant to the decisions which were being questioned, in

order to debate the motion. This would force the commissioner to defend his or

her record, and it would act as a powerful incentive to better administration

in the European Union. For, where there has been mismanagement, the

Commissioner might well be required to demonstrate to the European Parliament

that action had been taken to correct the mistake and to prevent any

recurrence, and that, of course, could involve calling officials in the

Commission to account for their mistakes, perhaps even subjecting them to

disciplinary procedures. Certainly, the European Parliament would need to be

assured that appropriate remedial measures had been taken. Thus, the principle

of individual ministerial responsibility could be a powerful tool of

accountability in the affairs of the European Union.

VI.

The European Union is, as we have seen,

based on conceptions of government that are outdated in the modern world of

assertive democracy. It was much influenced by the ethos

of 4th Republic France, which legitimised technocratic leadership,

and sought to insulate this leadership from effective parliamentary scrutiny;

and also by the ethos of consociational democracy which legitimised decision-making by elites, with the role of the electorate being confined to that of

ratifying these decisions. It is time

for these outdated conceptions to be replaced by the British ethos of

parliamentary government, which entails the collective responsibility of the

Commission to the European Parliament, and the individual responsibility of

individual Commissioners for mismanagement, incompetence or corruption.

But, even if such reforms were to be

implemented, the electors of the European Union might still feel that their

institutions were remote from them. For the key

decisions on European matters would still be made by political elites,

albeit accountable political elites.

Liberal constitutional theory, however,

suggests that power is entrusted to political elites, to legislators, by the

people only for certain specific purposes. "The Legislative", Locke

claims, "cannot transfer the power of making laws to any other hands. For

it being but a delegated power from the People, they who have it cannot pass it

to others".[6] That principle has been broadly accepted as a

constitutional convention in Britain, where major changes involving the

transfer of the powers of Parliament, either upward to the European Union, or

downwards, to devolved bodies in, for example, Scotland, Wales or Northern

Ireland, are thought to require endorsement through referendum.

Constitutional theory, then, seems to require

that the endorsement of the people is needed in a democratic polity when

sovereignty is transferred. That constitutional principle was well understood

by one of the founding fathers of the European Community, Altiero Spinelli, who

hoped that his proposed European Union could be worked out by a European

Parliament which had been granted a constituent mandate for that purpose

through a referendum.

The implication of this idea is that

constitutional changes in the European Union need to be endorsed not only the

parliaments of the member states, but also by the people. For the electors of

the member states, so it might be said, entrust their leaders with the powers

given to them by the Treaties; but they give them no authority to alter the

Treaties themselves. That authority can only be given through the expression of

popular wishes in a referendum. It would certainly concentrate the minds of

European leaders if they knew that constitutional amendments to the Union would have to be put, not just to the legislatures

of the member states, but also to the people in referendums.

Use of the referendum for major

constitutional changes in the European Union could perhaps be supplemented by

also using it for certain major policy issues. Why should not the Social

Chapter, for example, have been put to the European electorate for endorsement

in a referendum? Electors in the European Union would

have more reason to concern themselves with European issues if their vote was

needed to validate them. European Union-wide referendums might then do a

great deal to overcome the sense of alienation and remoteness felt by many

Europeans; and it could lead to greater identification on the part of the

European electorate with the European Union. But,

above all, introduction of European-wide referendums into the politics of the

European Union would be an explicit recognition of the principle of the

sovereignty of the people, a principle without which a united and democratic Europe cannot be built.

The challenge for the European Union, then,

is to find a means to bridge the gap between the machinery of policy-making,

which concentrates power in the hands of elites, and the ethos of democratic

self-government which entails popular control of institutions. That

challenge can only be met by introducing British ideas of responsible

government into the European Union, and by a measure of direct democracy,

intended not to replace the representative institutions of the Union, but to supplement them and help remedy their

deficiencies. A genuine European Union can only be built with popular

support. It cannot be built by holding the people at bay.

VII.

These ideas for making the government of the European Union more

accountable are based in part, of course, upon British constitutional

experience and the lessons to be drawn from it. But the European Union is not

likely to accept British ideas unless Britain can be persuaded to play a

more constructive part in European affairs. It is perhaps worth pondering on

the words spoken by Winston Churchill at the Albert Hall in 1947, when he

insisted that, "If Europe united is to be a living force, Britain will

have to play her full part as a member of the European family". These

words remain as true today as they were fifty five years ago.

Vernon

Bogdanor

September

2001

1 The idea of consociational democracy was

developed by the Dutch political scientist, Arend Lijphart. See, for example,

Democracy in Plural Societies: A Comparative Exploration, 2nd edition, Yale

University Press, 1977. Back

2 European Parliament: Committee on

Institutional Affairs: Draft Report on The Presidency of the European

Community. Part B: Explanatory Statement. PE 119.031/B. Para

6. Back

3 The German political scientist, Karlheinz

Reif, was the first to characterise European elections as "second-order

elections" in his book, Ten European Elections, Gower, 1985. Back

4 W E Gladstone, Gleanings from Past Years,

John Murray, 1879, vol 1, p 233. Back

5 A lurid account of alleged fraud in the

Commission, involving misappropriation of funds, corrupt dealings with

contractors and "jobs for the boys", is to be found in a book by Paul

Van Buitenen, formerly assistant auditor in the Financial Control Directorate

in Brussels, Blowing the Whistle; One Man's Fight Against Fraud in the European

Commission, Politico's, 2000. Back

6 John Locke, Second Treatise of Government,

para 141. Back